Three years ago, I was just a few days in to my very first ‘big person’ job. I was 23 years old. For the previous five years I had been studying (and, admittedly, partying) hard as a Psychology undergraduate and Behavioural and Economic Science postgraduate student. I had spent time working behind a bar to fund my studies (and my nights out), but beyond that I had no real experience of the professional world. So, to be perfectly honest, the reality of starting out as a graduate behavioural science consultant was daunting to say the least.

Since then, I’ve learned a lot about professional work, and particularly its differences to academia. Walking into the role, the dissimilarities became apparent almost instantly.

I think the simplest way I can put it is through an analogy – and I’ve been watching The Bear on Disney+ recently, so we’ll go with cooking. Imagine working in as a chef in Michelin star restaurant. The conditions are perfect. The surfaces have been scrubbed within an inch of their lives. Only the very best equipment is being used. The food is cut into precise measurements and plated up with a pair of tweezers. This is behavioural science in the academic world. When you apply behavioural science in the real world, you’re not working as a chef in a Michelin star restaurant. You’re cooking a roast dinner for a family of 10 in a one-bedroom flat with an oven that has one of its shelves missing. It’s untidy, unpredictable, and you can’t always do everything you want to do.

The reality of applied behaviour change, from my experience at least, is that it’s far from the exact science that much of its theory originates from. It’s not about running tightly controlled and closely monitored experiments to further our understanding of complex theories and behavioural models. There often isn’t the time, capacity, or budget to be entirely purist in our approach. Remember, you have to think about the meat, the potatoes, the gravy, the roast puddings, and the vegetables, all whilst catching up with your uncle. Working with clients, you need to keep things simple, balance multiple priorities, work to tight deadlines, and collaborate with people who may be sceptical of your methods (and that’s before you even get to the challenge of influencing the behaviours of diverse real-world populations).

So, if the application of behavioural science is so messy, how can we make sure it’s done effectively? This is something that we at Caja have been working to perfect for as long as I have been here – and we think we have a pretty good answer. When we apply nudge theory to influence real-world behaviours, we appreciate that we aren’t in the controlled world of academic research. Instead, we lean on methodologies from areas such as process improvement and project management to create a structured way of minimising the noise and maximising our impact, and we call it CognitivQI TM.

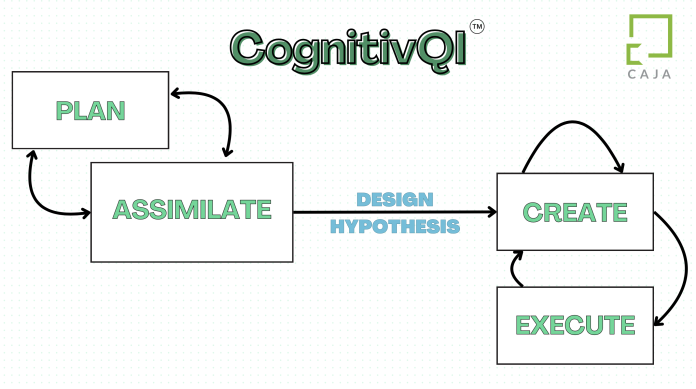

Our CognitivQI TM methodology has been refined through years of experience of changing behaviours across a range of contexts. It takes a phased approach to applying behavioural science across a traditional service improvement model and these phases work as follows:

Plan – Collaborating with clients to achieve clarity over the objectives of the project. Understanding who, what, and why we need to influence.

Assimilate – Gathering evidence around the behavioural challenge. Conducting quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis, guided by behavioural frameworks (e.g., COM-B) to better understand the current context.

Create – Using the evidence collected in the first two phases to develop a hypothesis for change and design our behavioural interventions and recommendations based on existing research evidence and experience from pervious projects.

Execute – Testing our interventions on a small scale, monitoring the results, and developing a plan for scale-up. Utilising the PDSA (Plan, Do, Study, Act) improvement cycle to support continuous improvement, whilst controlling for any unintended consequences.

By following this approach, we can start to bridge the gap between the Michelin star restaurant and our real-world one-bedroom flat kitchen. We account for the unpredictability of applied science by controlling what we can and testing our ideas, being aware that they might not work as planned first-time. Essentially, we find the best middle ground so we can create the most effective interventions possible – a fast-food restaurant kitchen, if you will.

To help more aspiring behavioural scientists discover the realities of applying nudge theory in the real world, we have developed the Caja Behavioural Science E-Learning Course, only on Udemy. If you are interested in learning more about applied behaviour change, or want to refresh your knowledge of basic behavioural science concepts, find it here: https://www.cajagroup.com/elearning-behavioural-science/